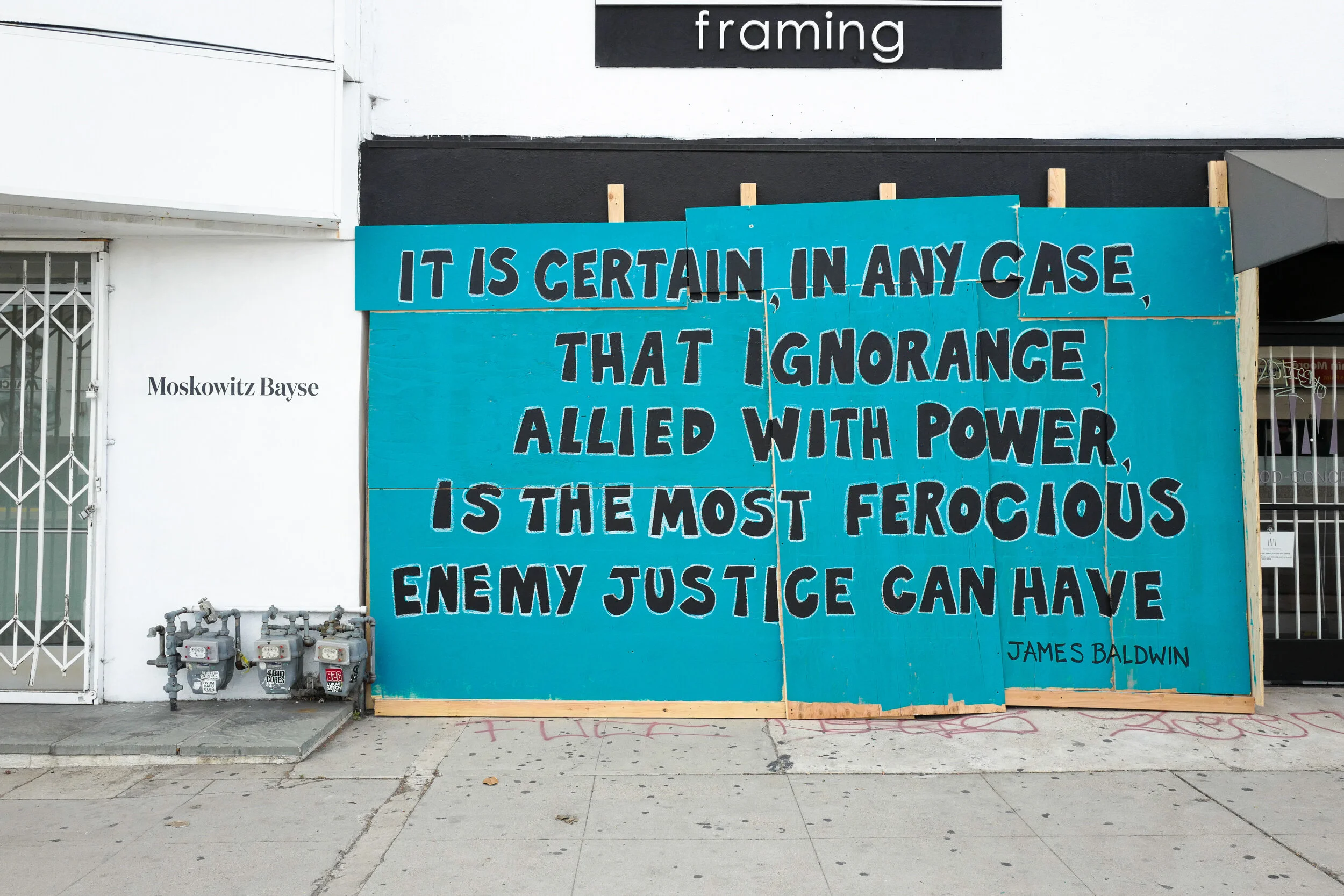

BLM

Los Angeles, CA 2020

-text below gallery-

BLM

October 30th, 2020

i. Historical Lineage of an Uprising/ii. Citizen Witness/iii. 'Tough on Crime'/iv. Black Lives Matter/v. The Murder of George Floyd/vi. Departure from the Past/vii. Progress or Gestures/viii. "A Responsibility"

i. Historical Lineage of an Uprising

The national uprising in support of the Black Lives Matter movement over the course of 2020 was in many ways a historical departure from the past—i.e. the massive scale and range of the protests themselves, the visible change in demographic participation, business, media and mainstream culture's empathetic response, as well as some evidence of constructive political reaction. Hopefully, we will also come to witness long term social and political changes as result of these mass demonstrations.

Yet, despite the distinctive character of the protests of 2020, they are very much a part of a historical lineage. The events hold reverberations of a past mired with the brutality of racism, as well as courageous activism, social progress hand in hand with prolonged setbacks, and the ruinous repeating theme of systemic violence breeding an anguished response of community violence.

A century ago, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) launched its national anti-lynching campaign. The demands in many ways echo the present. It was a call for the eradication of the unconstitutional extrajudicial murder of Black citizens and for the justice system to hold those who committed these crimes accountable. Thousands of lynchings were reported throughout the reign of Jim Crow; on average, a lynching took place every four days in the decades around the turn of the century.

In the midst of this campaign against lynching, the “Red Summer” of 1919 would erupt. As valiant Black veterans returned from World War I, their communities faced brutal attacks and lynchings by White mobs throughout the country in response to the perceived threats to Jim Crow order in the South and demographic changes in Northern cities due to the Great Migration. After fighting and sacrificing in the name of “freedom” abroad, Black veterans refused to be inert in the face of violent repression and second-class citizenship at home.

Armed and trained in combat, these men formed community defense organizations, applying tactics such as stationing protective snipers on neighborhood roofs to direct engagement with terrorizing White mobs, as well as local police who acted as an institutional arm in the racial repression. This bold veteran defense, itself part of a lineage of centuries of Black resistance in America, would most certainly not bring about an end to the violence targeting African-Americans, but historians would mark the summer as a turning point in how the Black community would manage and respond to racial terror and institutional repression thereafter.

As prototypical mob lynchings of the pre-WWII era declined though, many of the continued lynchings would be directly attributed to illegal police murders, often local sheriff's aiding in or carrying out racist vigilante killings themselves.

Activists worked tirelessly throughout the early decades of the 20th century to change this ongoing injustice. Despite high profile political endorsements and hearings held before the Senate Judiciary committee, multiple federal anti-lynching bills failed to become law throughout the era.

Then in 1955, the brutal lynching of 14 year-old Emmet Till and the subsequent acquittal of his murderers by an all White jury would become a symbol of the decades of racist murder, brutality and repression inflicted on the Black community. The event, seemingly like so many horrible racist murders before, would catalyze a seismic shift toward racial justice long overdue in our nation. The momentum and activism stemming from the murder would galvanize the early Civil Rights movement and materialize in the landmark Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of the 1960s, though no federal anti-lynching bill would ever become law. Great progress had been made, but in practice, the laws did little to quell the violent repression of Black citizens throughout the nation.

Several of the most infamous uprisings and/or race riots of the 1960s would emanate from incidents of police brutality and excessive force. In different regions of our nation, the large-scale destruction and loss of life experienced in Harlem, NYC in 1964, the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, CA in 1965, and in Newark, NJ and Detroit, MI in the summer of 1967 were all set off by similar events and circumstances: singular incidents of police violence. Each event seemingly like many before in these cities, would be the sparks to ignite the tinderbox of outrage in communities who had long been systematically trapped into a cycle of poverty, disenfranchisement and police repression.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. summarized the dynamic between the Black community, the police and society at large on his visit to Watts following the riots:

“... the Negro of the ghetto was convinced that his dealings with the police denied him the dignity and respect to which he was entitled as a citizen and a human being. This produced a sullen, hostile attitude, which resulted in a spiral of hatred on the part of both the officer and the Negro. This whole reaction complex was often coupled with fear on the part of both parties. Every encounter between a Negro and the police in the hovering hostility of the ghetto was a potential outburst....

The criminal responses which led to the tragic outbreaks of violence in Los Angeles are environmental and not racial. The economic deprivation, racial isolation, inadequate housing, and general despair of thousands of Negroes teaming in Northern and Western ghettos are the ready seeds which gave birth to tragic expressions of violence…”

Following the years of civil unrest in Black communities across America, President Lyndon B. Johnson's National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders released the Kerner report, a fact finding mission of what led to the violent rebellions. It outlined a "National Plan of Action" to quell community violence in response to systemic racism, calling for massive investment in education, employment, housing in African-American communities and, emphatically, police community relations. This report ordered by the White House itself, would unfortunately be ignored by the very same administration, and as time progressed, its prolific conclusions would continue to manifest themselves: "Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.”

In 1980, the brutal beating and killing of Arthur McDuffie in Miami, Florida would too result in widespread protest and civil unrest. During the investigation, several officers involved in the McDuffie killing departed from historical covenant and broke the “blue wall of silence” to testify against fellow officers in exchange for immunity. It was astounding evidence that seemed destined for convictions, yet all the officers involved would be acquitted. The community, to which this trial had become a symbol of the police repression they had long experienced, erupted in rage.

The sparks which led to the infamous civil unrest in Los Angeles in 1992 was the acquittal of four police officers who had been filmed brutally beating Rodney King. At the time, the rare capturing of such an event by a nearby witness with a VHS camcorder seemed to provide unique and overwhelming evidence to procure a conviction and gave hope to a new era of civil rights activists that the event would be a historical turning point for police accountability. The video evidence should have seemingly made the Rodney King case solid in its ability to convince of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, unfortunately, it was not.

Ibram X. Kendi would summarize the community response to the miscarriage of justice, “Black and Brown residents rushed to claim justice in the Los Angeles streets. They had reached their own verdict: the criminal justice system, local business owners, and Reagan-Bush economic policies were guilty as charged of robbing the poor of livelihoods and assaulting them with the deadly weapon of racism.” The televised uprising that followed would come to shape the cultural zeitgeist of the era.

At the turn of the millennia, New York City would endure several flagrant, racially-charged police killings and brutality cases. In 1997, the country was repulsed after reports were released that police officers in Brooklyn beat and tortured Abner Louima, by sodomizing him with a broomstick handle while handcuffed at the precinct. In 1999, the infamous “41 Shots” were fired at Amadou Diallo while attempting to retrieve his wallet in the vestibule of his home in the Bronx. In 2000, while on duty working as a security guard, a botched drug sting by undercover officers would leave Patrick Dorismond shot and killed in Manhattan. In 2006, Queens police would fire fifty bullets at the unarmed Sean Bell on the morning of his wedding day.

In a rare case of officers being held accountable by the courts, the offending officers in the Louima sexual assault were convicted, one sentenced to 30 years in prison without parole, though some charges were later appealed and overturned. But of the officers who were tried for the wrongful killings of the Black men in each of the other high-profile incidents, all would be acquitted. Large demonstrations throughout the city followed each acquittal and the events would be memorialized in the art and culture of the era.

In the midst of these events would be the largest civil unrest in America since Los Angeles in 1992. In April of 2001 in Cincinnati, Ohio, a White police officer shot and killed Timothy Thomas, a 19 year-old Black man, following a traffic stop. Thomas had been pulled over eleven times by different White officers in the previous two months and had been issued twenty-one citations for seat-belt and license violations, prompting the warrants for his arrest which lead to the fatal events. The discriminatory and often violent policing of the Black community was an immense point of contention in the city. In the six years prior to the event, fifteen Black men had died during interactions with the police in Cincinnati.

The event, like many before, would again be a match thrown on the tinder-box of racial discrimination, economic disenfranchisement and police repression suffered by those in the Black community of the city. Six days of civil unrest would follow. Large peaceful protests would coincide with fires, violent confrontation with police and hundreds arrested, including a non-lethal use of force by police during a procession the day of Thomas' funeral, injuring multiple children. In reaction to the events, a boycott of Cincinnati's downtown businesses was organized, including the cancellation of events by many famous Black entertainers, costing the city millions of dollars.

Though the “2001 Cincinnati Riot” would be the largest urban uprising since “1992 LA Riots,” it is largely forgotten in American collective memory. The events of September of 2001, would overshadow nearly all others of the time. Once again, the officer charged with negligent homicide of Thomas would too be acquitted.

An appalling incident in 1998 would provide a somber backdrop to all of the racially-charged incidents of the era and ring reverberations of NAACP's anti-lynching campaign initiated nearly a century earlier. James Byrd Jr., a Black man in Jasper, Texas accepted a ride home from three White men. The three avowed white supremacists that night brutally beat him, spray painted his face, chained him to the back of their truck and dragged him for three miles, dismembering and decapitating his body before dumping his torso in front of a Black cemetery. The heinous act shocked the nation: a lynching as America approached the new millennia.

In contrast to the aftermath of racially charged police killings of the era, the event would lead to both judicial and political ramifications. The three men involved would all be convicted of capital murder and it would be the first time in Texas history where White men were sentenced to death for killing a Black man. As with Emmet Till half a century earlier, Byrd's murder catalyzed efforts for political change, with the NAACP once again acting as leading advocates. The efforts would result in the Texas state legislature enacting the James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Act in 2001 and the Federal government passing the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act in 2009, signed by President Barack Obama.

The number of hate crimes committed would drop for years following the passing of the federal law, in hope that race relations were turning a corner during the first term of America's first Black president. But by the end of the next decade, the numbers of hate crimes had once again risen back to pre-2009 levels, with bias-motivated killings reaching an all time high. Maybe not coincidentally, the wave of deaths at the hands of police that would give rise to the Black Lives Matter movement would also erupt in these same years.

While America was willing and able to address the hate crimes of those with individual racists beliefs in a fairly bi-partisan manner, the killings committed by those representing our laws— government employees on duty to protect and serve— carried out in a social and political landscape developed out of eras of institutional racism, were something our nation had yet to find the courage to redress.

ii. Citizen Witness

Our country's violent historical lineage makes quite clear that police brutality is by no means a modern phenomenon in the Black community, but the prevalence of video documentation of this brutality by citizens of these communities is.

With the exception of per chance surveillance footage or strategically released police footage, video recounting of such events remained scarce over the nearly two decades following the Rodney King case. In this era, Americans were more likely to see televised incidents of violent police engagement in the form of popular entertainment in shows like “COPS.”

The 2010s would usher in an era of accessibility to cellular phone video recording. The widespread documentation that followed has helped broadcast to a national audience a glimpse of how truly common and horrific these incidents of police brutality and extrajudicial killings are in the Black community. The technology that gave rise to these bystander recordings, in conjunction with attempted reform efforts, would also lead to the patchwork implementation of police body camera use nationwide within the same decade; theoretically providing further documentation of potential police misconduct. But in appalling historic consistency, the modern wave of video evidence, to date, has yet to correspond with any meaningful shift in accountability for excessive violence by police. With few exceptions, prosecutors and juries remain just as impotent to indict or convict as in previous decades, despite the mounting video evidence provided against officers. The general public’s regular viewing of horrific killings of Black citizens has since become commonplace in the news cycle over the last decade, as has the expectation that little to no justice will come to the families of these victims.

Our judicial system applied to officers of the law defies logic. The hard evidence provided in most of these high profile police brutality cases would surely lead to the conviction of an average citizen. But the same evidence leveraged against someone wearing a badge does not carry the same result. There are legal arguments made and specific statutes that uniquely apply to the profession which are cited as the justification for these non-convictions, but common sense, common decency and democratic principles maintain the contrary.

Over recent decades, much of America has come to regretfully accept, willingly ignore or rationalize away this charade of justice. But in so doing, inadvertently or not, it has maintained the fatal consequences of this system. When the most egregious cases of police brutality cannot produce justice, they set a modern precedent that police are essentially untouchable by our legal system. And with this, the United States justice system continues to exhibit its inability to uphold the basic human rights of African-American citizens at the hands of the police.

The defiant posture and expression of Officer Chauvin as he looked into the camera that was capturing him kneeling on George Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes, until his last breath, was of a man who was not worried about being held accountable for his actions. His behavior was an embodiment of the racial injustice that continues to be structurally ingrained into our system. These incidents of police brutality and the legal paradigm that is unwilling to hold them accountable does not exist in a vacuum; they are the result of centuries of racial injustice in our country.

After hundreds of years of brutality unjustly waged on Black people in this nation, American society has still managed to maintain the fallacy that they are in fact the ones to be feared. Despite the continued struggle for its eradication, racism has proven to be quite resilient in the face of changing times.

iii. 'Tough on Crime'

Indisputably, astounding progress has been made in the fight for racial equality over the last century in our nation. The "Black experience" in our country, as with every other race and ethnicity, is anything but narrow and there is no singular narrative for what it means to be Black in America. Yet, the reality is there very much continues to be unfortunate common experiences that apply to those with a darker skin complexion in our nation. In many cases, the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Policing practices in communities of color over the last hundred years transformed from the explicit discriminatory enforcement of the pre-Civil Rights Era to the seemingly race-neutral targeting of those same communities under policies like the “War on Drugs,” creating an era of what Michelle Alexander, in her monumental work of the same name, would testify to being The New Jim Crow. In the book, Alexander references studies that repeatedly show that White and Black people use and sell drugs at very much the same rates —White people are actually statistically more likely to engage with narcotics. Yet, the drug war was violently waged in the Black community, with arrest and conviction rates for small drug possession charges eclipsing those in the White community, in some states at 25 to 50 times the rate of White people.

Our government, under both Democrat and Republican leadership alike, monetarily incentivized local police departments to prioritize this continued biased assault on these communities, and these agencies became increasingly militarized as the decades passed. Various “tough on crime” policies carried out by both political parties over the last several decades were often aimed at capitalizing on the racial fear and resentment in much of White America that had been increasingly stoked by biased media, demographic changes, civil rights laws and the effects of a rapidly changing economic landscape.

The cumulative results have most certainly contributed to our current landscape, where Black Americans die at the hands of the police by nearly three times the rate of White Americans.

Though many of these same politicians now condemn the militaristic tactics and biased policing that they were once proponents, even architects of—Presidential Nominee Joe Biden possibly being the most high profile example of this political evolution—this about-face does very little to undo the years of trauma, lives lost and families destroyed by the public policy that they propped up and from which local police often took their direction. They have also done little to change that today the justice system in many communities of color is functionally different than in White communities; often, the experience is more akin to the lack of rights endured by those living outside of a constitutional democracy.

It would be disingenuous to claim that the violence the Black community has suffered at the hands of police is solely the result of biased individual officers, though this most certainly is a factor. Rather, the scourge of violent police confrontations is very much the result of decades of institutional direction and systemically biased public policy. Chronic over-policing and enormous law enforcement spending in these communities over the decades have also done little to eliminate the violent crime suffered by the citizens who live in these often low-income communities, though violent crime is often cited as the principle justification for the contentious police presence.

Many officers, who enter the difficult profession and attempt to carry out their duties with the most admirable of intentions, must so commonly find themselves in the defeated realization that they have been assigned to work within a broken system that only perpetuates an unjust status quo. They are endlessly tasked to tamp-down recurring symptoms, but are unable to make any real dent in the root of the disease: poverty and eras of systemic disenfranchisement.

iv. Black Lives Matter

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement came into existence with the goals of organizing and protesting against racially motivated violence against Black people in response to the acquittal of the man who pursued, shot and murdered Trayvon Martin, an unarmed, African-American 17 year old. Alicia Garza, a domestic workers' advocate, Patrisse Cullors an anti-police-brutality activist and Opal Tometi, an immigrant rights activist, collaborated to create the online platform that would become #Black Lives Matter. The movement increasingly gained momentum and spread awareness through the effective use of social media. Following a string of publicized slayings of Black men at the hands of the police between 2014 and 2016 (notably the killings of Eric Garner in New York, Michael Brown in Missouri, Laquan McDonald in Illinois, Tamir Rice in Ohio, Walter Scott in North Carolina, Freddie Gray in Maryland, Sandra Bland in Texas, Alton Sterling in Louisiana, and Philando Castile in Minnesota) the movement garnered national attention during resulting nationwide protests and as well as the civil unrest that erupted in the cities of Ferguson, MO and Baltimore, MD.

For a variety of reasons, the movement during those years was not particularly well supported by the White general public. Conservative politicians labeled the movement as an anti-police hate group and many liberal politicians softly denounced or distanced themselves from the movement. The movement’s existence also inspired the reactionary countermovement, All Lives Matter, who propagandized that BLM believed Black lives were superior to other lives and promoted killing police, instead of the reality: that they were fighting for equal humanity and absolutely did not promote violence against police.

One of the most visible play-outs of the political backlash to BLM during this era was NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling during the national anthem to protest racial injustice and police brutality. Much of White America proceeded to collectively lose their minds over the act and it, not what he was protesting, soon became the political controversy of the day. Kaepernick was branded as dishonoring the troops, which led to him being blacklisted by NFL owners, prematurely ending his professional football career. The NFL owners also threatened to fine any players who followed suit.

Only four years later, following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, the NFL would, as an institution, publicly come out in support of BLM, with overt encouragement of their players voicing their opinions and peacefully protesting. “End Racism” was painted at the backline of end zones and teams held demonstrations in solidarity during the national anthem, with many players kneeling in protest across the league. It would also, not coincidentally, be the season where the now Washington Football Team would finally drop the racial epithet from its club name. This was an astounding organizational about-face. The historical change of context may have already begun to erase the scarlet letter placed on Kaepernick, just as time transformed the historical opinions of Muhammad Ali’s political protest 50 years earlier.

Though an extraordinary change of attitude, the powers-that-be at the NFL likely did not make these public changes out of a newfound awakening to racial injustice, though we hope some may have. More likely they changed due to increased pressure by the leagues majority African-American players and their union, as well as their supportive coaches. But maybe even more likely, that the NFL calculated that much of White America, their main cash cow, had changed their sentiments on the matter.

v. The Murder of George Floyd

The general public’s response in the weeks following the release of the heartbreaking video of George Floyd being slowly asphyxiated to death was a historical departure, particularly for White America. The immediate aftermath was covered by the media in the same sensationalized approach they have traditionally taken in covering these disturbingly common events: down-play the recurring tragedy in the Black community, call into question George Floyd’s character, and underreport the arising peaceful protest movement that is calling for reform, while emphasizing the examples of looting and public destruction that followed. These usual reflexes touted by government figures and the media have, to our historical detriment, traditionally allowed for much of America’s majority White society to believe that the brutal actions of the police must have been justified or to excuse the incident as another one-off, “bad apple” officer and dismiss the Black communities' cries of injustice as opportunistic or exaggerations, despite what their eyes have repeatedly seen.

This time, in the weeks following George Floyd’s killing, much of the White general public instead got behind the reignited BLM movement and widely empathized with their message. They seemed to finally arrive at what the activists of the movement had been saying since its inception: that they were not anti-police, but anti-police brutality; that they were not attempting to destroy America but protesting a system and police culture that shielded officers from legal accountability in the face of unwarranted brutality and the heinous extrajudicial killing of Black Americans. The momentum and kinship that grew out of the BLM movement in Minneapolis in late May 2020, would lead to the largest protests in American history in the following summer months, with protests supporting BLM taking place in every state in our country. The public outcry led to the exposure of a stream of horrific but previously less publicized incidents that further reaffirmed the public’s demand for change, notably the incomprehensible killing of Breonna Taylor by police in her home earlier that spring. The movement that summer also shed much needed light on the unreported violence and high murder rate suffered by Black transgender women, with much of the movement embracing the increasingly inclusive slogan “All Black Lives Matter.” The movement began to stimulate difficult and long overdue conversations about systemic racism and bias in our society. As a result, many formerly apolitical organizations, small businesses and large corporations alike, began to scramble to show their alliance with the BLM movement. In Los Angeles, many storefronts were simultaneously boarding up their windows in fear of looting, while also spray painting words of support for the movement on their newly constructed plywood barriers.

The massive peaceful protests were unfortunately unaccompanied by violent civil unrest, looting, arson and vandalism. Though the acts were objectionable, it is always stunning that our society seems surprised when communities who have repeatedly been subjected to violence, will in response eventually erupt in violence or when those who have long been systematically looted, in cathartic rage, also loot. The prevalence of these destructive elements were small compared to the massive peaceful protests regularly taking place, but they were enough for many state and local governments to justify citywide curfews, deployment of the national guard and an increased militarization of local police. As a result, peaceful demonstrators protesting police brutality were very much confronted with police brutality.

Historically, the results of this destructive form of social protest would lead to the negative societal outcomes Dr. King illustrated after the Watts riots, “Violence only serves to harden the resistance of the white reactionary and relieve the white liberal of guilt, which might motivate him to action and thereby leaves the condition unchanged and embittered.”

But again, instead of the incidents of destruction and confrontations undercutting mainstream White society's empathy and support, as it often has in the past, most supporters remained unclouded in their continued belief in the cause behind the protests and strongly renounced the excessive force used on protesters across the country.

vi. Departure from the Past

What changed between these two waves of BLM that resulted in such different responses in a span of just 5 years? The video of George Floyd being slowly murdered was absolutely agonizing to witness, but it was certainly not the first time the majority of White society has been confronted with the horrors of police brutality toward African-Americans on the news. There are obvious factors that very likely contributed to this outstanding change in sentiment: first, the Presidency of Donald Trump and second, COVID-19, as well as one less obvious but always present factor —time.

President Trump unearthed a racist nerve in this country that many hoped we had left buried in history. To many people’s dismay, he didn’t even have to dig very far to expose it. The volatility of his Presidential actions also made it nearly impossible to stay in a state of apolitical existence, forcing many to confront political issues that they were once able to mostly ignore. It is very possible that his fierce positioning against the BLM movement was enough for the millions of White Americans who despised the President to boldly support a cause he was so vigorously disavowing. His order to violently clear and tear gas peaceful protestors for a photo-op in Washington D.C. only added fuel to this fire. For many, his rhetoric and actions may have also simply clarified the real virtue of the BLM movement’s cause.

COVID-19 and its resultant stay-at-home order in much of the country drastically changed people's use of time and left many more unemployed, further amplifying our already economically stratified society. People across the country had been maintaining the pulse of the news in hopes of hearing whispers of the end of the pandemic or if another toilet paper shortage was on the horizon. It would seem this pent up energy and anxiety was no longer containable with the anger that was felt as millions were faced with repeatedly watching the video of George Floyd’s murder.

But maybe, it just takes time for social consciousness to change. It is an inconvenient truth, but a truth nonetheless. Our still very much segregated society contributes White America’s difficulty in empathizing with the experience of other races in our country; leaving many White people in a simultaneous state of knowing and unknowing of the injustice suffered. White society at large was well aware of the suffering of Black Americans under Jim Crow, but it took a barrage of violent television coverage of the repression and murdering of civil rights protestors, white supremacist terrorism and the assassination of President Kennedy before it was just barely able to garner the political support needed for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This is often the case with just about all progressive social movements in our country: the struggle is long and there are many who suffer while the general public slowly catches on to what is at stake and politicians muster up the courage to take the political risk to do what is right.

Or maybe perhaps, people had very much recognized and understood our society’s injustices, but had felt insignificant, helpless, in being able to change such tremendous problems until a path in how they can potentially help do so was clearly presented. This is what sometimes allows for an incident that is seemingly like many before to be the spark that awakens a sleeping giant.

vii. Progress or Gestures

There were many immediate effects on local public policy throughout the country during, and following, the public pressure campaign under the umbrella Movement for Black Lives, some of them reforms and mainstream policy debates that would have been unthinkable only a year earlier.

Throughout the country there have been local victories in the banning of chokeholds, restrictions on lethal force, banning of tear gas and rubber bullet use on protesters, the banning of no-knock warrants, disciplinary reforms, transparency of police records, increased bias training, prosecutorial reform in ‘“use of force” cases resulting in death, the rise of progressive district attorneys, divestment of bloated policing budgets in order to invest in the needs of communities of color, proposals to end or limit qualified immunity, the expanded decriminalization of marijuana possession and requirements for police to intervene and report the excessive force of fellow officers, just to name a few.

Conversations about alleviating the role police have been unfairly asked to take on in our communities have also begun. In the absence of public funding for an adequate number of social workers, societal issues like homelessness, addiction and mental health crises have become day to day responsibilities of the police, which have an assortment of damaging effects on our society.

Many positive changes have been successfully demanded, but the system that allowed for this brutality to persist with little consequence is very much still in place. We have yet to see if any of the officers involved in these high profile incidents will truly be held accountable for their actions and, if they are, will their convictions and the array of local reforms have true effects on policing moving forward? The historical pattern does not lend well to optimism, though this moment does feel different. In the same accord, will the private sector policy changes that flourished to align with the movement and promote economic justice in the Black community result in measurable progress or come to reveal themselves as token gestures?

We have unfortunately already seen some waning of support from the once enthusiastic White public since the wind-down of the largest of protests. Fears stoked by phrases like “defund the police” were again used as tools to undermine support and many worried that a new backlash to the movement would reinvigorate Trump supporters enough to send him into a second term in the upcoming fall elections. Throughout our modern era, White society has had the luxury of not being directly affected by this systemic violence, and, as it has happened many times in the past, once resolute allies to the cause may allow justice for the Black community to again be put on the backburner for what is argued to be political prudence. It speaks to the sentiment of a quote by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., “This 'Wait' has almost always meant 'Never'. We must come to see, with one of our distinguished jurists, that justice too long delayed is justice denied.”

The re-election of Trump would most certainly come with an attempted reinforcement of the biased system in place, but it is yet to be seen if Democrats at the Federal level will have the political will or courage to prioritize making true reforms to policing or our judicial system overall. Though some recent progress has been made, the track record over the last several decades does not bode well. It is always difficult to maintain widespread public momentum and support for a cause, even when it does manifest in such astounding force. One would hope that the events of the summer of 2020 will act as a turning point, a touchstone that we will be able to look back at, when our country took another step forward in making good on its promises of freedom, liberty and justice. But the Civil Rights movement teaches that every step is a fight and holding those steps gained can be just as challenging.

The Black Lives Matter movement is the keeper of the flame of the Civil Rights movement in the 21st century, though many attempt to put space in between the two, so as to not give BLM the legitimacy it deserves. The lens with which our society has looked back on the Civil Rights movement is certainly rose colored. Politicians, the media and much of mainstream White society at the time often denounced the actions of the Civil Rights movement, as well as its hallowed leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as communist, of a criminal element and being run and inflamed by outside agitators trying to destroy America. If it wasn’t so harmful and effective, it would be almost comical how very little this rhetoric has changed in the last 60 years. We can only hope its potency has begun to wear out.

viii. "A Responsibility"

In the middle of the intersection of Cynthia and San Vicente in West Hollywood, a momentary break was called after hours and miles of protesting that hot afternoon in early June (not long after turning around at the border of Beverly Hills in order to avoid a confrontation with the wall of police across Sunset Blvd who were brandishing guns loaded with rubber bullets there to greet protestors for the enforcement of a tactically called 2pm curfew that was established just prior to their arrival). A group of young African-American organizers used the moment to speak to the large crowd who kneeled around them. They spoke about the importance of what we were all there protesting and how positive and peaceful the energy was, despite the awful events that brought everyone into the street. One African-American woman while speaking said “Thank you to our White allies for standing and marching with us today,” to which a White woman in the crowd replied, “You don’t have to thank us. We have a responsibility to be here!”

Sources

Henry Hampton et al. "Awakenings, 1954-1956," Eyes on the Prize, Volume 1, pt. 1(Alexandria, VA: PBS Video, 2006) DVD.

Victor Luckerson, "New Report Documents 4,000 Lynchings in Jim Crow South," Time, 2/10/15, https://time.com/3703386/jim-crow-lynchings/

Adam Fairclough, Race & Democracy: The Civil Rights Struggle in Louisiana (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1995)

Beth Tompkins Bates, Pullman Porters and the Rise of Protest Politics in Black America 1925-1945, (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001)

Abigail Higgins, “Red Summer of 1919: How Black WWI Vets Fought Back Against Racist Mobs,” History, 7/26/19, https://www.history.com/news/red-summer-1919-riots-chicago-dc-great-migration

Brad R. Tuttle, How Newark Became Newark: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of an American City, (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rivergate Books, 2009)

Henry Hampton et al. "The Keys to the kingdom, 1974-1980," Eyes on the Prize, Volume 3, pt. 7(Alexandria, VA: PBS Video, 2006) DVD.

LA 92, Daniel Lindsay, T.J. Martin, (US: National Geographic, April 28, 2017) Digital Stream

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, (New York: The New Press, 2010)

Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive Guide to Racist Ideas in America, (New York: Bold Type Books, 2016)

Jim O'Grady and Beth Fertig, “Twenty Years Later: The Police Assault on Abner Louima and What it Means,” WNYC News, 10/9/17, https://www.wnyc.org/story/twenty-years-later-look-back-nypd-assault-abner-louima-and-what-it-means-today/

Ese Olumhense, “20 Years After the NYPD Killing of Amadou Diallo, His Mother and Community Ask: What's Changed?” New York/Intelligencer, 2/1/19, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2019/02/after-the-nypd-killing-of-amadou-diallo-whats-changed.html

Julian Borger, “New York on edge as police kill unarmed man in hail of 50bullets on his wedding day,” The Guardian, 11/27/06, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/nov/27/usa.julianborger

Thomas J. Lueck, “Bell Protesters Block Traffic Across City,” The New York Times, 5/7/08, https://archive.nytimes.com/cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/05/07/protesters-assail-acquittal-of-officers-in-sean-bell-case/

Howard Wilkinson, “It's Been 20 Years Since The 2001 Civil Unrest in Cincinnati,” 91.7 WXVU News, 4/5/21, https://www.wvxu.org/local-news/2021-04-05/its-been-20-years-since-the-2001-civil-unrest-in-cincinnati

Robert E. Pierre, “Racial Strife Flares in Cincinnati Over Downtown Business Boycott,” The Washington Post, 4/2/02, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2002/04/02/racial-strife-flares-in-cincinnati-over-downtown-business-boycott/3011f511-0b80-4e20-8afc-ac3eb77c80c8/

“James Byrd Jr's killer executed for notorious 1998 hate crime,” BBC, 4/25/19, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-48040916

Meredith Worthern, “James Byrd Jr.,” BIOGRAPHY, 7/16/20, https://www.biography.com/crime/james-byrd-jr

Hannah Allam, “FBI Report: Bias-Motivated Kilings At Record High Amid Nationwide Rise IN Hate Crime,” NPR, 11/16/20, https://www.npr.org/2020/11/16/935439777/fbi-report-bias-motivated-killings-at-record-high-amid-nationwide-rise-in-hate-c

Brita Belli, "Racial disparity in police shootings unchanged over 5 years," Yale News, 10/27/20, https://news.yale.edu/2020/10/27/racial-disparity-police-shootings-unchanged-over-5-years

"About", Black Lives Matter, 1/22/14, https://blacklivesmatter.com/about/

Baltimore Rising, Sonja Sohn, HBO Films, (US: HBO, November, 20, 2017) Digital Stream

Linda Poon and Marie Patino, “Rodney King to Tyre Nichols: A Timeline of U.S. Police Protests,” Bloomberg, 6/9/20, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-06-09/a-history-of-protests-against-police-brutality

Jeremy Hobson,"After 9 High-Profile Police Involved Deaths of African-Americans, What Happened To The Officers?" WBUR, 7/11/16, https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2016/07/11/america-police-shooting-timeline

Susan T. Gooden & Samuel L. Myers, Jr. "The Kerner Commision Report Fifty Years Later: Revisiting the American Dream" The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, September 2018, 4 (6) 1-17; https://www.rsfjournal.org/content/4/6/1

Jack Moore, "'A form of punishment': Colin Kaepernick and the history of blackballing in sports," The Guardian, 3/22/17, https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2017/mar/22/colin-kaepernick-blacklisted-history-sports

Darryl C. Murphy, "Philly City Council passes ban on use of tear gas, rubber bullets on protesters," Plan Philly, WHYY, 10/29/20, https://whyy.org/articles/philly-city-council-passes-ban-on-use-of-tear-gas-rubber-bullets-at-protests/

Justin Carissmo, Zoe Christen Jones, "California bans chokeholds, shortens probation sentences and moves to independently probe police," CBS NEWS, 10/1/2020 https://www.cbsnews.com/news/california-chokeholds-shorter-probation-sentences-independent-police-investigations/

Barbara Campbell, Suzanne Nuyen, "No-knock Warrants Banned In Louisville In Law Named For Breonna Taylor," NPR, 6/11/20, https://www.npr.org/sections/live-updates-protests-for-racial-justice/2020/06/11/875466130/no-knock-warrants-banned-in-louisville-in-law-named-for-breonna-taylor

India L. Sneed, "New York State Police and Criminal Justice Reforms Enacted Following George Floyd's Death," GreenberTraurig, 6/24/20, https://www.gtlaw.com/en/insights/2020/6/new-york-state-police-and-criminal-justice-reforms-enacted-following-george-floyds-death

Ryan Grim, Akela Lacy, "Progressive Prosecutor Movement Makes Major Gains In Democratic Primaries," The Intercept, 8/6/2020, https://theintercept.com/2020/08/06/district-attorney-races-progressive-prosecutors/

City News Services, "LA Council Approves Plan for Spending $56.6M Diverted From LAPD," NBC 4, 5/25/21, https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/la-council-approves-plan-for-spending-56-6m-diverted-from-lapd/2603632/

"Gov. Lee Announces Law Enforcement Reform Partnership," TN Office of the Governor, 7/2/20, https://www.tn.gov/governor/news/2020/7/2/gov--lee-announces-law-enforcement-reform-partnership.html

Lisa Kashinsky, "Warren, Markey, Sanders introduce bill to end qualified immunity," Boston Herald, 7/1/20, https://www.bostonherald.com/2020/07/01/warren-markey-sanders-introduce-bill-to-end-qualified-immunity/

Martin Luther King, Jr., "Letters from Birmingham Jail", The Atlantic Monthly, August, 1963, v. 212, https://www.csuchico.edu/iege/_assets/documents/susi-letter-from-birmingham-jail.pdf

King in the Wilderness, Peter Kunhardt, (Kunhardt Films, HBO, April 2, 2018) Digital Stream

Michael Eric Dyson, April 4, 1968: Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Death and How it Changed America, (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2008).

“Chapter 27: Watts,” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute,Stanford, 07/07/2014:https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/publications/autobiography-martin-luther-king-jr-contents/chapter-27-watts